Convex Hull Construction

Constructing the Hull by the Monotone Chain Algorithm

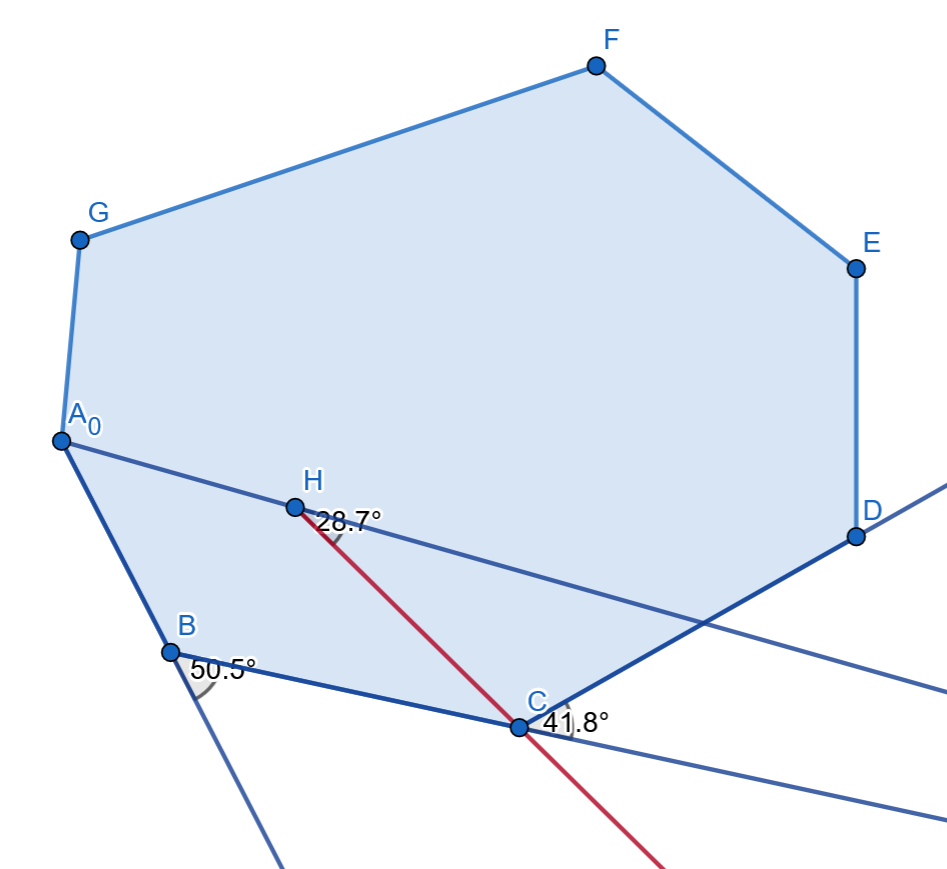

An intuitive property of the convex hull is that while we go counter clockwise around the edges, the edges themselves form a counter clockwise rotation. This means that construction itself should be done so that this property holds. Refer to the diagram below:

The $A_0 \to B \to C$ path is valid, and creates a convex hull. However, $A_0 \to H \to C$ path is invalid, since $C$ lies out of the hull that $A_0 \to H$ attempted to create.

There will be a few ways to go about using this property, but we will use it by constructing a lower hull and upper hull. This is because the transition from an increasing x to a decreasing x is annoying to implement, so we’ll just construct the bottom half and upper half separately before combining. The lower hull can be constructed as mentioned by iterating through dots along x and trying to main a CCW angle among the vertices contained in the hull, and we can do something similar for the upper hull by iterating through dots along x but this time looking for clockwise. Later on we’ll account for the reversed order when combining these two into our hull.

To do this, a prerequisite is that we sort the points $(x,y)$ by smaller x, and when x are the same smaller y. The smaller x part should be more obvious, since we want to iterate through points with increasing x. The smaller y actually doesn’t seem to matter at first, but it does since we only want the vertices of the hull, not all points on the hull when we reach a sort of ‘wall’. This will make more sense after reading through this, and imagining an example of a square with multiple vertices along each edge.

Now about the detailed process, starting with the lower hull. We start from our leftmost point, and iterate through points. We attempt a try - where we see if our selected point belongs in our hull. If it satisfies CCW with the last two points, we can add it in, and that’s simple. However let’s say we found a point that is CW, which means it is located out of the hull in the current construction. We can’t just ignore this and continue on, instead we need to somehow modify what we currently have so that this point can be included in the vertices of the convex hull. To do this, we will pop the edges until we let the CCW hold. This is because the popping simply means that the popped points are now inside the polygon, and we can try to increase the angle until the aforementioned point is included. We can do this for all sorted points. It’s also okay to do this for points that would be on the upper hull, since these are all popped while we construct the lower hull anyways. Note that when there’s less than 2 points in the hull, we can add without checking CCW.

We can do the exact same thing for the upper hull by simply replacing CCW with CW, and all that’s left is combining the two. The first obvious step is that we have to add the points in the upper hull in reverse to keep an order of CCW points of the convex hull. We also need to note that there will be duplicates for endpoints, for both leftmost and rightmost points in the lower and upper hull. We can do this by creating a new container, adding points in the lower hull excluding the last one, and then adding the points in the upper hull in reverse and also excluding the leftmost one (the one where index = 0 before reversing). There are of course more ways to write this but I found this method most intuitive.

However in terms of accounting for cases when a hull isn’t formed, and to make the code look cleaner, personally I prefer to set hull = lower hull, and add all points in the upper hull excluding the endpoints. This is explained in more detail below in the polygon formation check.

P.S. If you want to include points that are on the borders of the hull that don’t really contribute to the hull itself, you can replace the CCW conditions to include = 0. Also, now is a nice time to think of that square example to see how it behaves on walls. Also note that this doesn’t check the most basic conditions where a polygon doesn’t form in the first place (e.g. when it’s a line)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

sort(pts.begin(), pts.end());

vector<pii> botHull, topHull;

for(pii pt : pts){

while(botHull.size()>=2 && CCW(botHull.end()[-2], botHull.end()[-1], pt) <= 0) botHull.pop_back();

botHull.push_back(pt);

while(topHull.size()>=2 && CCW(topHull.end()[-2], topHull.end()[-1], pt) >= 0) topHull.pop_back();

topHull.push_back(pt);

}

vector<pii> hull = botHull;

for(int i=topHull.size()-2;i>0;i--) hull.push_back(topHull[i]);

cout<<hull.size();

Polygon Formation Check

A thing worth noting is when the problem doesn’t assure you that the points are given non-colinearly. If all points are colinear, then it will not form a polygon, and your “hull”, which is not even a proper hull will be duplicates. It’s nice to know if your hull functions, and if not, it should at least not have duplicates.

A very intuitive way is to sort the points in your polygon, remove duplicates, and see if the size is below 3. But that ruins the order of our points we put so much effort into keeping.

The checking itself can be done by simply checking if the size of the hull ≤ 4 since that means there are only 2 points in the hull, excluding left right duplicates. The way we constructed the hull only accounts for two endpoints given a series of colinear points anyways, so if all points are colinear, the bottom hull and top hull will have those two endpoints only. Additionally, note that our hull construction still holds, in a way that it forms a chain or a single dot instead.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

if(botHull.size() + topHull.size() <= 4){

//means that this is not a polygon, just a chain

//hull can still at least represent the chain

}

vector<pii> hull = botHull;

for(int i=topHull.size()-2;i>0;i--) hull.push_back(topHull[i]);

cout<<hull.size();